http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3224-8858

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3224-8858

by Paul Murrell

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3224-8858

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3224-8858

Version 3: Monday 13 January 2020

Version 1: original publication

Version 2: fixed up 'gridExtra' citation

Version 3: update pdf.js code (for displaying PDFs)

This document

by Paul

Murrell is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This report describes several R packages that allow HTML content to be rendered as part of an R plot. The core package is called 'layoutEngine', but that package requires a "backend" package to perform HTML layout calculations. Three example backends are demonstrated: 'layoutEngineCSSBox', 'layoutEnginePhantomJS', and 'layoutEngineDOM'. We also introduce two new font packages, 'gyre' and 'courier'.

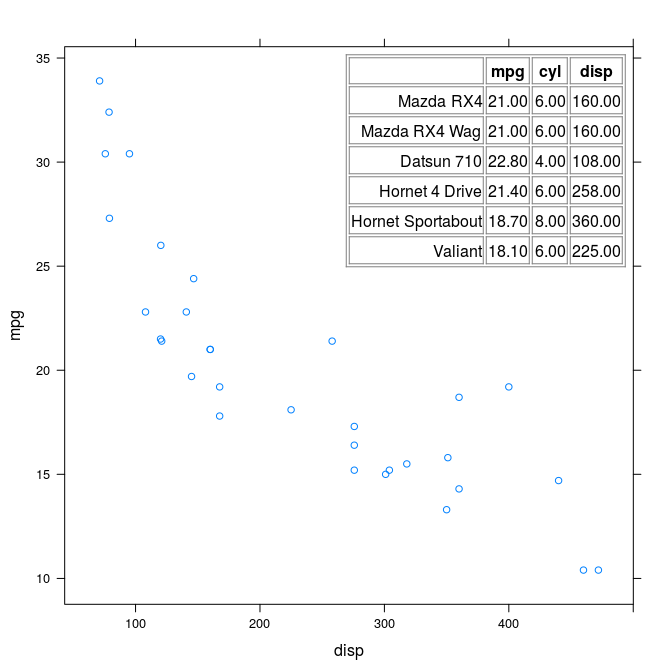

The aim of the 'layoutEngine' package is to support rendering of HTML content within R graphics (R Core Team, 2018). The following code provides a simple demonstration. We start with a standard 'lattice' plot (Sarkar, 2008).

library(lattice)

xyplot(mpg ~ disp, mtcars)

Next, we generate some HTML, in this case using xtable

from the 'xtable' package (Dahl, 2016).

library(xtable) html <- print(xtable(head(mtcars[1:3])), type="html", print.results=FALSE)

Finally, we navigate to the main 'lattice' panel viewport

and call grid.html from the 'layoutEngine' package

(Murrell, 2018d),

using the 'layoutEnginePhantomJS' backend

(Murrell, 2018g),

to render the HTML table (in the top right corner of the plot).

library(layoutEnginePhantomJS)

downViewport("plot_01.panel.1.1.vp") grid.html(html, x=unit(1, "npc") - unit(2, "mm"), y=unit(1, "npc") - unit(2, "mm"), just=c("right", "top"))

We could do the same thing in a single step using a 'lattice' "panel function". The following code produces exactly the same result as the plot above.

xyplot(mpg ~ disp, mtcars, panel=function(...) { panel.xyplot(...) grid.html(html, x=unit(1, "npc") - unit(2, "mm"), y=unit(1, "npc") - unit(2, "mm"), just=c("right", "top")) })

The next two sections describe the main functions in the 'layoutEngine' package through a series of examples. Subsequent sections go into the underlying design details of the package.

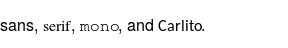

One reason for creating the 'layoutEngine' package is to be able to generate graphics that are easy (or easier) to describe in HTML compared to R graphics.

For example, in R graphics, we can normally only draw text with a single

font face. The following code uses grid.html

to draw text containing plain, italic, and bold

font faces.

grid.html("<p>plain, <em>italic</em>, and <strong>bold</strong></p>")

The above example is actually possible in R graphics if we (mis)use a mathematical expression, like this ...

grid.text(expression(paste("plain, ", italic(italic), ", and ", bold(bold))))

... but something that really is not possible in R graphics is the

use of more than one font family in a single piece of text. The

following code shows how we can do this with

grid.html.

Rfonts <- c("sans", "serif", "mono", "Carlito") CSSfonts <- cssFontFamily(Rfonts) grid.html(paste0('<p><span style="font-family: ', CSSfonts["sans"], '">sans</span>, ', ' <span style="font-family: ', CSSfonts["serif"], '">serif</span>, ', ' <span style="font-family: ', CSSfonts["mono"], '">mono</span>, and ', ' <span style="font-family: ', CSSfonts["Carlito"], '">Carlito</span>.'), fonts=Rfonts)

The code above demonstrates an important point about using

grid.html. If we are rendering HTML that includes text

content, we must specify the fonts that we are using for that text.

This font specification must happen in R, via the fonts

argument to grid.html,

and in CSS within the HTML that we are rendering,

typically via style attributes,

and those specifications must match. The

cssFontFamily function can be used to map R fonts

to CSS fonts to make sure that we are specifying the same font in

both R and CSS. The Section on Defining fonts contains much more

information on this topic. We did not have to specify any fonts in the

previous examples because grid.html defaults to using

a "sans" font.

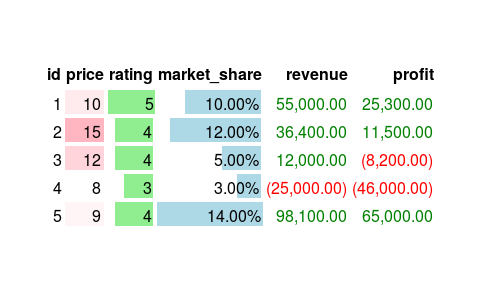

The introduction showed another example use of 'layoutEngine', which is to take advantage of the typesetting features of HTML to arrange text in a table, especially when packages like 'xtable' have already been written to generate the required HTML. The following code shows a more complex table example from the 'formattable' package (Ren and Russell, 2016).

library(formattable)

products <- data.frame(id = 1:5, price = c(10, 15, 12, 8, 9), rating = c(5, 4, 4, 3, 4), market_share = percent(c(0.1, 0.12, 0.05, 0.03, 0.14)), revenue = accounting(c(55000, 36400, 12000, -25000, 98100)), profit = accounting(c(25300, 11500, -8200, -46000, 65000)))

sign_formatter <- formatter("span", style = x ~ style(color = ifelse(x > 0, "green", ifelse(x < 0, "red", "black"))))

table <- formattable(products, list( price = color_tile("transparent", "lightpink"), rating = color_bar("lightgreen"), market_share = color_bar("lightblue"), revenue = sign_formatter, profit = sign_formatter))

grid.html(as.character(table))

The result of the rendering in the example above is not exactly the same

as the rendering that a browser produces. The layout of the table

is correct and the colours are correct, but in the browser the

coloured backgrounds are rounded rectangles (because the

HTML that 'formattable' generated uses the CSS

property border-radius). This imperfect rendering reflects

the fact that the 'layoutEngine' package currently only supports

some basic CSS properties. For much more information on the limitations

of the 'layoutEngine' package, see the Discussion Section.

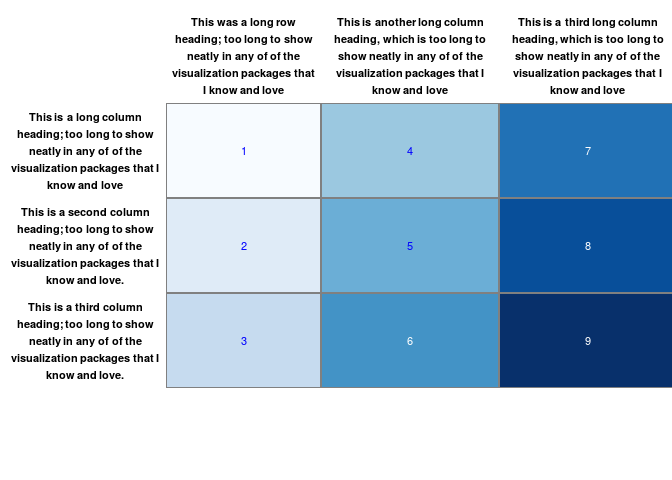

In a DisplayR Blog post, Tim Bock extolls the relative simplicity of generating tables in HTML, using an example that required wrapped text for both row and column headers. In his post, he provided code for generating the HTML table from R; the following code renders that HTML code back in R graphics.

options(layoutEngine.backend=phantomjsEngine) html <- readLines("displayr.html") htmlDoc <- htmlDocument(html) grid.html(htmlDoc)

The new feature in the code above is a call to the htmlDocument

function. This alternative to the htmlElement function

is intended

for when we have a complete HTML document (rather than just

an HTML fragment) that we want to render in R. We have to call

htmlDocument explicitly because grid.html

assumes that character input is only an HTML fragment (and

calls htmlElement itself).

Drawing tables of values can be achieved

directly in R graphics

(e.g., using grid.table from the 'gridExtra' package;

Auguie, 2017),

but HTML (combined with CSS) provides many other typesetting

features that are not covered by R graphics packages.

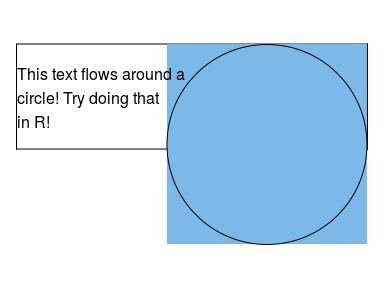

The following code shows an example of the CSS shape-outside

property

(combined with the float property), which allows us to

flow text around a non-rectangular shape (in this case a circle).

For this example, we switch to the 'layoutEngineDOM' backend

(Murrell, 2018f)

because the 'layoutEnginePhantomJS' backend does not support

the shape-outside property. The 'layoutEngineDOM'

backend provides access to the default system web browser (which

is a recent Firefox for this report), which means that we can gain access

to the most recent CSS properties.

library(layoutEngineDOM) ## Give browser plenty of time to do its work options(DOM.limit=10) html <- c('<div style="width: 350px; border-width: 1px; border-style: solid">', '<div style="background-color: #7db9e8; width: 200px; height: 200px; float: right; shape-outside: circle()"/>', '<p>This text flows around a circle! Try doing that in R!</p>', '</div>')

grid.html(html)

The real value of being able to render HTML content in R is not just so that we can reproduce what would appear in a browser. This facility becomes more useful when we combine the HTML content with other graphical output that R is good at, such as plots. An example of this was shown in the introduction, where an HTML table was drawn within a 'lattice' plot. This section demonstrates some other possibilities.

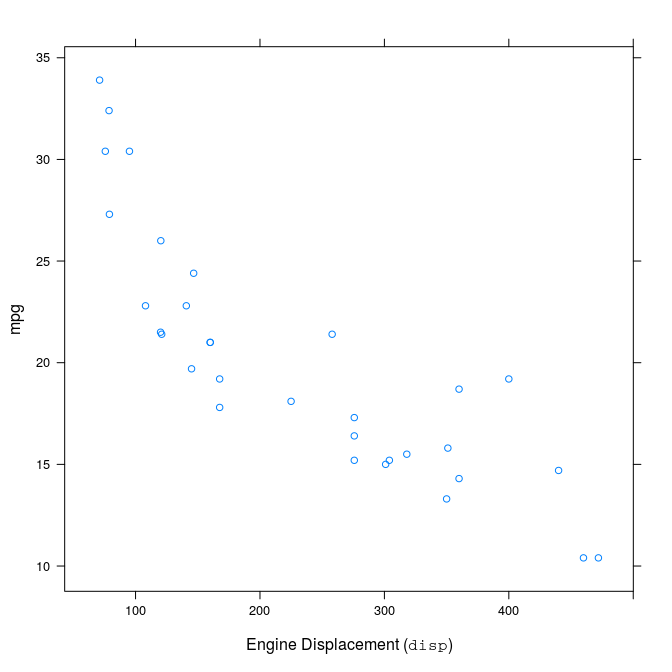

The code below uses HTML rendering to provide a plot axis label

for a 'lattice' plot that contains more than one font

(the R variable name is drawn with a typewriter font).

One difference about this code is the use of

htmlGrob rather than grid.html

because we need to specify the label to xyplot as a

'grid' grob (rather than just draw it immediately).

We also call the flow function to lay out the HTML content

and pass that to htmlGrob (rather than passing the

raw HTML). This is because xyplot queries the

label grob several times (e.g., for its height and width) and we do

not want to have to perform the HTML layout for every query.

The Section on The lower-level interface discusses the flow

function in more detail.

For this example, we switch to the CSS Box backend, 'layoutEngineCSSBox' (Murrell, 2018e). We use this backend for this example because it produces a better result than the PhantomJS backend and it is "quieter" than the 'DOM' backend. The Section on 'layoutEngine' backends discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the different backends in more detail.

library(layoutEngineCSSBox) html <- paste0('<span>Engine Displacement ', ' (<span style="font-family: ', CSSfonts["mono"], '">disp</span>)', "</span>") flowedHTML <- flow(html) xyplot(mpg ~ disp, mtcars, xlab=htmlGrob(flowedHTML))

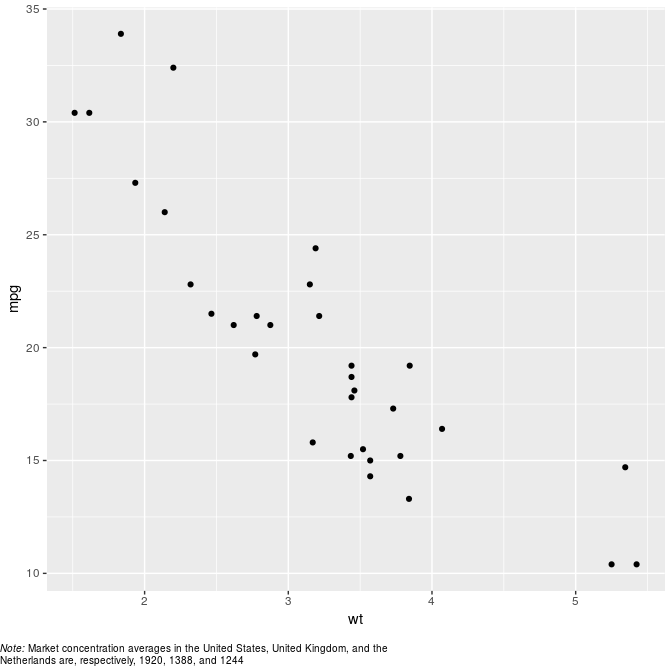

The next example, from a Stack Overflow post,

is very similar. This example involves adding a caption to a

'ggplot2' plot (Wickham, 2016), using

gridExtra::grid.arrange to arrange the

plot above the caption.

The caption

does not involve multiple font families, but

it does involve multiple font faces and it involves

text split across two lines

(which is a step too far for R's limited plotmath facility).

This is a good example of a typesetting task that looks very simple,

and is simple in HTML, but is not normally possible in R graphics.

library(ggplot2) library(gridExtra)

note <- ' <p style="font-size: 7.5pt; line-height: 0.8"> <span style="font-style: italic">Note: </span> Market concentration averages in the United States, United Kingdom, and the <br> Netherlands are, respectively, 1920, 1388, and 1244 </p> ' gg <- ggplot(mtcars, aes(wt, mpg)) + geom_point() caption <- htmlGrob(flow(note)) grid.arrange(gg, bottom=caption)

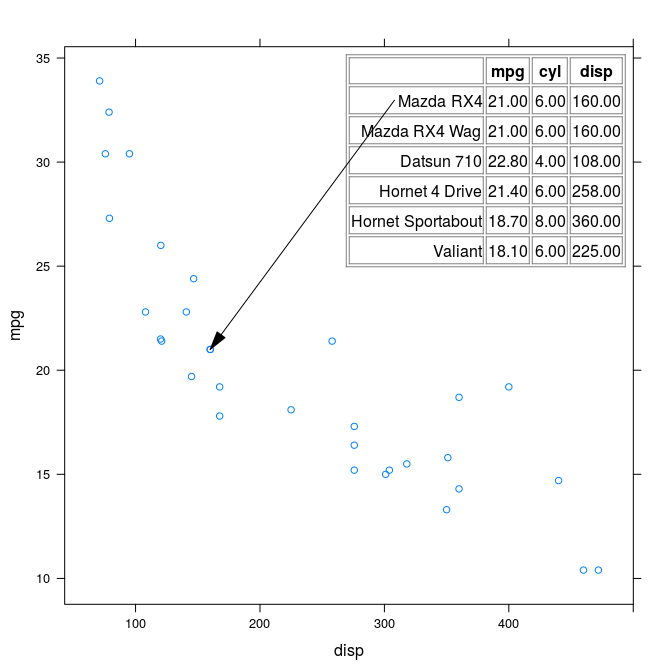

The next example demonstrates that, having rendered HTML content in R (with 'grid') in combination with an R plot (based on 'grid'), it is possible to make use of 'grid' tools to further integrate the HTML output with the R plot output. In the following code, we draw a 'lattice' plot, add an HTML table at the top-right of the plot, then draw an arrow from the left edge of a piece of text within the HTML table to the corresponding data point within the 'lattice' plot.

options(layoutEngine.backend=phantomjsEngine) xyplot(mpg ~ disp, mtcars) html <- print(xtable(head(mtcars[1:3])), type="html", print.results=FALSE) flowedhtml <- flow(html) downViewport("plot_01.panel.1.1.vp") grid.html(flowedhtml, x=unit(1, "npc") - unit(2, "mm"), y=unit(1, "npc") - unit(2, "mm"), just=c("right", "top"), viewports=TRUE) grid.move.to(mtcars$disp[1], mtcars$mpg[1], default.units="native") upViewport(0) vp <- grid.grep("TD.+SPAN.+vp", grep=TRUE, viewports=TRUE) downViewport(vp) arr <- arrow(ends="first", angle=15, length=unit(5, "mm"), type="closed") grid.line.to(unit(-1, "mm"), .5, arrow=arr, gp=gpar(fill="black"))

There are a couple of interesting features in the code above.

One new feature is the use of viewports=TRUE in the

call to grid.html. This means that, in addition to

drawing the HTML content, 'grid' viewports are created that correspond

to each piece of HTML content. This is what allows us to use

grid.grep to find the viewport that corresponds to

the first <SPAN> element within a <TD> element

within the HTML table (so that we can navigate down to that viewport

to specify one end of the arrow).

Another feature is the use of the flow function.

The reason for calling flow in this example

is slightly different than the previous one. This time we are making

sure that the 'grid' grobs and viewports that are created when the

HTML content is rendered are visible on the 'grid' display list

(so that we can navigate to the viewports that correspond to the

HTML content to add drawing). If we just passed the raw HTML directly

to grid.html, we would have had to call grid.force

(and trigger another HTML layout calculation) in order to make the

'grid' grobs and viewports visible on the 'grid' display list.

The Section on The lower-level interface explains the difference between

flowed HTML and raw HTML in more detail.

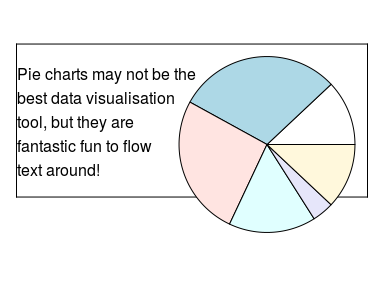

The next example also demonstrates the use of viewports=TRUE

to generate 'grid' viewports from HTML content.

This example is a variation on the example from the previous section

that used shape-outside to flow text around a

non-rectangular shape.

This time, rather than specifying a circle to flow text around,

we will specify an image, and the image will be an R plot

(a pie chart). We specify a transparent background for the image

because shape-outside flows text around the non-transparent

component of the image.

pie.sales <- c(0.12, 0.3, 0.26, 0.16, 0.04, 0.12) png("assets/pie.png", width=200, height=200, bg="transparent") par(mar=rep(0, 4)) pie(pie.sales, radius=.95, labels=NA) dev.off()

The following code uses HTML to flow text around the pie chart, then navigates to the <div> that was flowed around and draws the R pie chart within the corresponding viewport.

options(layoutEngine.backend=DOMEngine) ## Give browser plenty of time to do its work options(DOM.limit=10) html <- c('<div style="width: 350px; border-width: 1px; border-style: solid">', '<div id="pie" style="width: 200px; height: 200px; float: right; shape-outside: url(assets/pie.png)"/>', '<p>Pie charts may not be the best data visualisation tool, but they are fantastic fun to flow text around!</p>', '</div>') flowedhtml <- flow(html, assets=file.path(getwd(), "assets", "pie.png")) grid.html(flowedhtml, viewports=TRUE) vp <- grid.grep("pie", grep=TRUE, grobs=FALSE, viewports=TRUE) downViewport(vp) library(gridGraphics) grid.echo(function() { par(mar=rep(0, 4)) pie(pie.sales, radius=.95, labels=NA) }, newpage=FALSE)

One interesting feature of the code above is that we have HTML content

that refers to an external resource: the file assets/pie.png.

In order to layout this sort of HTML, we must use the assets

argument to flow, so that the layout engine can find

the external resource. This only applies when we are dealing with resources

on the local file system; external resources (URLs) should be resolved

by the layout engine. If we provide raw HTML directly to

grid.html, we can supply the assets argument there

instead.

Another detail about the code above is that we must use the 'gridGraphics'

package (Murrell and Wen, 2018)

to draw the pie chart because the 'layoutEngine' package

works in the 'grid' graphics sytem and the pie function

is based on the 'graphics' system.

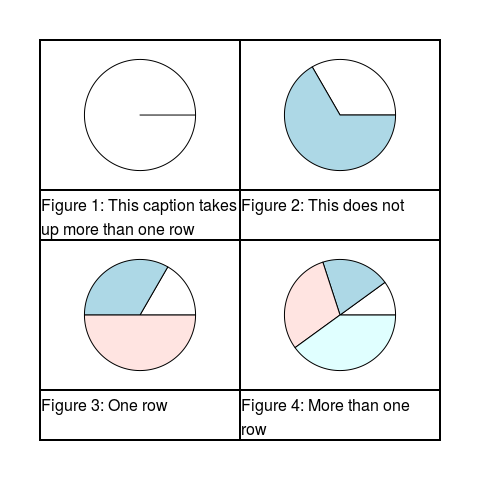

The next example further embraces the use of 'grid' viewports based on an HTML layout. In this example, we use CSS Grid Layout (Atanassov et al., 2018) to produce an arrangement of regions and then draw R plots within those regions. The following code describes HTML that contains a set of <div> elements, some of which are empty (we will use those to draw plots), and some of which contain text captions. This is followed by CSS code that specifies the layout of the <div> elements, which consists of two columns and four rows, where the heights of the second and fourth rows are based on the size of the text captions.

Having rendered this combination of HTML and CSS, we navigate to the empty <div> viewports and draw an R plot in each one. We switch back to the 'layoutEngineDOM' backend because we need support for CSS Grid Layouts.

options(layoutEngine.backend=DOMEngine) html <- ' <div id="main"> <div id="fig1"></div> <div id="fig2"></div> <div id="caption1"> Figure 1: This caption takes up more than one row </div> <div id="caption2"> Figure 2: This does not </div> <div id="fig3"></div> <div id="fig4"></div> <div id="caption3"> Figure 3: One row </div> <div id="caption4"> Figure 4: More than one row </div> </div> ' css <- ' div { border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; } #main { width: 400px; height: 400px; display: grid; grid-template-columns: 1fr 1fr; grid-template-rows: repeat(2, 1fr auto); grid-auto-flow: row; } ' flowedhtml <- flow(html, css=css) grid.html(flowedhtml, viewports=TRUE) figvps <- grid.grep("fig", grep=TRUE, global=TRUE, grobs=FALSE, viewports=TRUE) for (i in 1:4) { downViewport(figvps[[i]]) grid.echo(function() { par(mar=rep(0, 4)); pie(1:i, labels=NA) }, newpage=FALSE) upViewport(0) }

This layout would be tricky-to-impossible with a 'grid' layout because the heights of the second and fourth rows depend on the number of lines in the typeset text captions.

A new feature in the code above is the

css argument in the call to flow.

This is how we can provide CSS code separately from HTML code

for laying out HTML content.

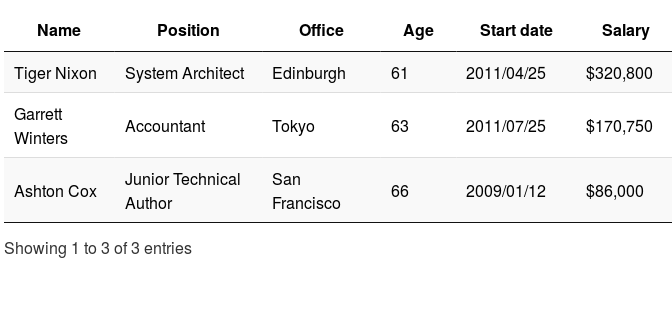

The next example further emphasises the value of using a web browser as the backend. In this example, we render a complete HTML page that contains a table that is styled and augmented by the DataTables javascript library (Jardine, 2014). Most of this result is just CSS, but the "3 of 3 entries" line below the table is generated by javascript code. This demonstrates the idea that we can benefit from a backend that can evaluate javascript code to render HTML content that is (even partially) generated by a javascript library.

htmlDoc <- htmlDocument(readLines("DataTable.html")) grid.html(htmlDoc)

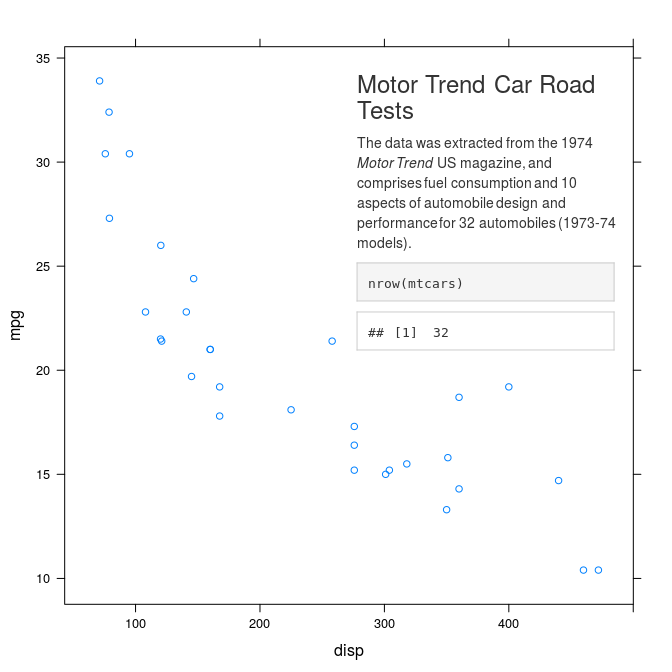

The final example really mixes things up. This time, to generate HTML content, we use an (admittedly trivial) R Markdown document (shown below).

### Motor Trend Car Road Tests

The data was extracted from the 1974 _Motor Trend_ US magazine, and

comprises fuel consumption and 10 aspects of automobile design

and performance for 32 automobiles (1973-74 models).

```{r}

nrow(mtcars)

```

The 'rmarkdown' package (Allaire et al., 2017) is used to produce HTML, including running the embedded R code and including the R output in the final HTML, then that HTML is rendered at top-right within a 'lattice' plot.

library(rmarkdown) render("example.Rmd", "html_document")

options(layoutEngine.backend=phantomjsEngine) html <- readLines("example.html") htmlDoc <- htmlDocument(html) xyplot(mpg ~ disp, mtcars, panel=function(...) { panel.xyplot(...) grid.html(htmlDoc, x=unit(1, "npc") - unit(1, "mm"), y=unit(1, "npc") - unit(1, "mm"), width=unit(3, "in"), just=c("right", "top")) })

This ends the high-level examples that demonstrate basic usage of the 'layoutEngine' package. The remaining sections delve into the underlying design of the package and lower-level details of how things work.

A fundamental requirement of the 'layoutEngine' package is that exactly the same fonts are used both to layout HTML content in a backend engine (e.g., 'layoutEngineCSSBox') and to render the HTML content in R. This is a requirement because the layout of HTML content in almost all cases will depend on the typesetting of text within HTML containers (paragraphs, table cells, etc). If the fonts do not match exactly, the rendered text in R will not align with other rendered HTML content (e.g., table borders). This section describes how this matching is achieved in the 'layoutEngine' package.

Because the end goal is to render content in R graphics, we want to start with an R font specification and map that to a CSS font specification. A font specification in R consists of a font family name (e.g., "Carlito"), a font face (plain, bold, italic, or bold-italic), and a font size (e.g., 12pt).

In HTML, the font used for text can be controlled by the CSS

properties font-family (e.g., "Carlito"),

font-weight (e.g,

"bold" or "normal"), font-style (e.g., "italic" or "normal"),

and font-size (e.g., 12pt) (and

font-variant, but we are going to ignore that).

The 'layoutEngine' package assumes that the HTML content that is to be rendered either contains no font family information or only font families that map to R fonts

A complication is the fact that HTML and CSS are designed to be flexible with respect to fonts so that a web browser can render content with whatever fonts are available. For example, the following CSS specification means that Helvetica will be used if it is available, then DejaVu Sans if it is available, then finally whatever sans-serif font the web browser can get its hands on.

font-family: Helvetica, DejaVu Sans, sans

By contrast,

we want to tell the 'layoutEngine' backend to use an exact font,

so instead we generate a CSS @font-face rule. This allows

us to specify an actual font file and associate it with a

font family and other properties. For example, the following

CSS specifies very precisely that the font family "TeXGyreHeros",

with normal style and bold weight, corresponds to the font file

found at the location assets/qhvb.pfb (relative to

the location of the HTML document).

@font-face {

font-family: "TeXGyreHeros";

font-style: normal;

font-weight: bold;

src: url('assets/qhvb.pfb');

}

In order to generate an @font-face rule, we need to

know the location of the font file that we want to use.

The 'layoutEngine' package makes use of the 'gdtools' package

(Gohel et al., 2018)

and the 'extrafont' package (Chang, 2018) to achieve this.

library(gdtools) library(extrafont)

The sys_fonts function from the 'gdtools' package

is useful because it provides information about system fonts,

including the location of font files.

sf <- sys_fonts() head(sf[c("family", "weight", "slant", "file")])

family weight slant file 1 Gillius ADF 200 100 /usr/share/fonts/truetype/adf/GilliusADF-BoldItalic.otf 2 STIXIntegralsUpD 200 0 /usr/share/fonts/opentype/stix/STIXIntegralsUpD-Bold.otf 3 STIXIntegralsD 200 0 /usr/share/fonts/opentype/stix/STIXIntegralsD-Bold.otf 4 Latin Modern Sans 200 0 /usr/share/texmf/fonts/opentype/public/lm/lmsans10-bold.otf 5 Lato 210 100 /usr/share/fonts/truetype/lato/Lato-BlackItalic.ttf 6 Roboto 50 100 /usr/share/fonts/truetype/roboto/hinted/Roboto-LightItalic.ttf

This is useful for rendering HTML on R graphics devices that are

based on Cairo graphics

(Packard et al., 2018), such as the default screen device

on Linux and the cairo_pdf device, because on those devices

we can specify a system font just by its family name (e.g., "Gillius ADF";

look at the 'g' in the output below).

cairo_pdf("cairo-font.pdf", width=1, height=.5) grid.text("Testing", gp=gpar(fontfamily="Gillius ADF")) dev.off()

Unfortunately, specifying fonts on the standard pdf

graphics device (and the postscript device) is less

straightforward; we have to use the Type1Font function

to associate

AFM files with a font family name and then call pdfFonts

(or postscriptFonts) to register the font for use with R.

The 'extrafont' package makes this easier with its functions

font_import and loadfonts, which automatically

register system fonts. The fonttable function can then

be used to provide information about registered fonts, including

the locations of font files.

ft <- fonttable() head(ft[c("FamilyName", "Bold", "Italic", "fontfile")])

FamilyName Bold Italic fontfile 1 Caladea TRUE FALSE /usr/share/fonts/truetype/crosextra/Caladea-Bold.ttf 2 Caladea FALSE TRUE /usr/share/fonts/truetype/crosextra/Caladea-BoldItalic.ttf 3 Caladea FALSE TRUE /usr/share/fonts/truetype/crosextra/Caladea-Italic.ttf 4 Caladea FALSE FALSE /usr/share/fonts/truetype/crosextra/Caladea-Regular.ttf 5 Carlito FALSE FALSE /usr/share/fonts/truetype/crosextra/Carlito-Regular.ttf 6 Carlito TRUE FALSE /usr/share/fonts/truetype/crosextra/Carlito-Bold.ttf

The only problem is that 'extrafont' only registers TrueType system fonts.

However, 'extrafont' also provides a font_install function that

can be used to load special font packages and those can contain

Type 1 fonts. As examples, the

'gyre' package (Murrell, 2018c) has been created to bundle the

TeX Gyre fonts

(Hagen et al., 2006, Hefferon, 2009)

and the 'courier' package (Murrell, 2018a) bundles

the IBM Courier font (IBM Corporation, 1990).

The following code repeats the text-with-multiple-font-families

example from earlier, but performs the rendering on the standard

pdf device. This requires the 'gyre' and 'courier'

packages to be loaded. Notice also that the mappings from R fonts

to CSS fonts has to be recalculated because we are rendering

to a different graphics device than before.

library(gyre) library(courier)

pdf("multifont.pdf", width=3, height=.5) CSSfontsPDF <- cssFontFamily(Rfonts) grid.html(paste0('<p><span style="font-family: ', CSSfontsPDF["sans"], '">sans</span>, ', ' <span style="font-family: ', CSSfontsPDF["serif"], '">serif</span>, ', ' <span style="font-family: ', CSSfontsPDF["mono"], '">mono</span>, and ', ' <span style="font-family: ', CSSfontsPDF["Carlito"], '">Carlito</span>.'), fonts=Rfonts) dev.off() embed_fonts("multifont.pdf")

A final wrinkle is that in R it is possible to specify one of three

generic font families: "sans", "serif", and "mono".

In order to map these to a specific font (that both R and CSS will use),

the 'layoutEngine' package uses match_family from the

'gdtools' package (on Cairo-based devices,

this is after first mapping "sans" to "Helvetica", "serif" to

"Times", and "mono" to "Courier", to match what R graphics

does internally).

The cssFontFamily function from the

'layoutEngine' package can be used to show how an R font family

maps to a CSS font-family, though the mapping is

dependent on the graphics device in use.

cssFontFamily(c("sans", "serif", "mono"), device="pdf")

sans serif mono "TeXGyreHeros" "TeXGyreTermes" "Courier"

cssFontFamily(c("sans", "serif", "mono"), device="cairo_pdf")

sans serif mono "TeX Gyre Heros" "TeX Gyre Termes" "Courier"

In summary, when we call grid.html (or flow),

we must specify which fonts we want to use by providing one or more

R font family names (the default is just "sans"). These

font family names are converted to CSS @font-face rules

that associate a CSS font-family with an exact font file.

For this to work (because we need paths to font files),

we must only use R font family names that exist

within the gdtools::sys_fonts font table (for Cairo-based

devices) or within the extrafont::fonttable font table

(for pdf or postscript). For cairo-based

devices we should be able to use any system font. For pdf

or postscript we can use any TrueType system font

and we can add further Type 1 fonts creating

a font package or making use of an existing font package

like 'gyre' or 'courier'.

When we are working with a pdf or postscript

graphics device, it is a good idea to embed fonts in the final document

(using extrafont::embed_fonts), otherwise we risk all

of our hard work being undone if a PDF viewer cannot find the fonts

that we have used and is forced to substitute different fonts.

In addition to providing exact font specifications in CSS

@font-face rules, we need to specify which font is

to be used for text within the HTML content that we wish to render.

By default, a CSS rule is added that specifies the <body>

font to be

the first font given in the fonts argument

to grid.html (or flow), something like

the CSS code below.

body { font-family: "TeXGyreHeros" }

The default behaviour has been set up so that, on Linux at least, the default font used for HTML layout matches the default font used by R graphics. For example, in the very first plot in this report, the font used in the 'lattice' plot and the font used in the HTML table that is added to the plot are identical.

When we generate HTML code with more than one font family,

we must use cssFontFamily to determine the

correct font-family to use within our HTML code.

In addition to needing the font to be identical for both HTML layout and R rendering, for drawing text output, we need to know how text has been broken across lines (when that happens).

This is not a problem for the 'layoutEngineCSSBox' backend because that generates separate layout information for each line of text. However, for backends built on web browser layout engines ('layoutEnginePhantomJS' and 'layoutEngineDOM'), extra work is required.

The problem is that, while web browser layout engines provide an API for querying the bounding box for laid out text, they do not provide an API for querying exactly where each letter or word of the text has been placed.

The solution adopted by both 'layoutEnginePhantomJS' and 'layoutEngineDOM' is to wrap each individual word of text content within a <span> element. This means that we can obtain the layout information for each individual word, though it also means that each individual word is drawn separately when the text is rendered in R.

The high-level interface provided by the 'layoutEngine' package

means that we can simply call grid.html and provide

it with raw HTML code and it will be rendered. This

section looks at the lower-level functions that underly that

convenient interface and provide finer control of the process.

The 'layoutEngine' package internally works with HTML as an

"htmlElement" object.

All raw HTML code passes through the

htmlElement function to turn it into a list containing an

"xml_document" object, optionally including CSS code

(within a <head> element), and any external assets.

html <- htmlElement('<p><img src="assets/pie.png"/>test</p>', css="p { text-align: center }", assets="assets/pie.png") html

$doc

{xml_document}

<html>

[1] <head>\n<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8 ...

[2] <body><p><img src="assets/pie.png">test</p></body>

$assets

[1] "assets/pie.png"

attr(,"class")

[1] "htmlElement" "htmlDocument"

It is assumed that the HTML content says nothing about which font

family to use for text - that is supplied in the next step,

when the HTML layout is calculated - but it is expected that

the HTML content may

contain font-weight, font-style, or

font-size styling, either explicitly or implicitly

(e.g., via a <th> element).

If the HTML content does contain font-family styling,

it is assumed that it will match one of the fonts supplied in the

HTML layout step.

It is also possible to call htmlDocument instead

of htmlElement, if our HTML code is a complete

document, rather than just an HTML fragment.

Once we have an "htmlElement" object, we can call

the flow function to generate layout information.

We can specify the size of the page for the layout, but it defaults

to the current 'grid' viewport size. We can also specify

the fonts at this stage so, for simple HTML content at least,

it is possible to generate different layouts by specifying different

fonts. The mapping of fonts to CSS depends on the R graphics device

we want to render onto, so we can also specify the intended

output graphics device, though this defaults to the currently active

graphics device. Finally, we can specify which backend layout engine

we want to use. This is set by default when a backend package is

loaded, but it can be overridden.

The result of an HTML layout is a "flowedhtml" object,

which contains layout information for each node within the HTML content

(both elements and text nodes). This is a mixture of location

information and styling information. The location information

is in px units, which is interpreted as 1/96in.

The layout information also includes a unique name for each node, which is used to name 'grid' grobs and viewports during rendering.

flow(html)

type name x y width height baseline text

2 P BODY.1.P.1 8.0000 8 672.00000 205 NA <NA>

3 IMG BODY.1.P.1.IMG.1 231.1094 8 200.00000 200 NA <NA>

4 SPAN BODY.1.P.1.SPAN.2 431.1172 189 25.76562 24 NA <NA>

5 TEXT BODY.1.P.1.SPAN.2.TEXT.1 431.1172 189 25.76562 24 5 test

family bold italic size color backgroundColor borderLeftWidth

2 <NA> NA NA NA <NA> #00000000 0

3 <NA> NA NA NA <NA> #00000000 0

4 <NA> NA NA NA <NA> #00000000 0

5 TeX Gyre Heros FALSE FALSE 12 #000000FF <NA> NA

borderTopWidth borderRightWidth borderBottomWidth borderLeftStyle

2 0 0 0 none

3 0 0 0 none

4 0 0 0 none

5 NA NA NA <NA>

borderTopStyle borderRightStyle borderBottomStyle borderLeftColor

2 none none none #000000FF

3 none none none #000000FF

4 none none none #000000FF

5 <NA> <NA> <NA> <NA>

borderTopColor borderRightColor borderBottomColor

2 #000000FF #000000FF #000000FF

3 #000000FF #000000FF #000000FF

4 #000000FF #000000FF #000000FF

5 <NA> <NA> <NA>

The main rendering work horse is the htmlGrob function;

the grid.html function calls htmlGrob

and draws the resulting grob. The htmlGrob function

will accept raw HTML code or a "flowedhtml" object.

In the latter case, a 'grid' gTree with all of its child grobs

and child viewports is generated. In the former case, a

'grid' gTree is created with just the HTML code, plus font, device,

and backend engine information; generation of child grobs is

delayed until rendering time. The difference is that, in the former case,

the HTML will reflow (the layout will be recalculated) every time that

the gTree is drawn (or queried). This means that the HTML can be

redrawn within different contexts and it will adapt to those contexts,

but it will also reflow unnecessarily within the same context (e.g.,

if it is queried repeatedly for its size).

Put another way, the HTML layout becomes fixed when the

flow function is called. If we know the context in which

we want to draw the HTML content, we should call flow

and pass the result to htmlGrob. On the other hand,

if we want to use the HTML layout within different contexts, we

should pass raw HTML code to htmlGrob.

The 'layoutEngine' package provides the main interface for laying out and rendering HTML content in R, but it relies on a backend package to perform the actual HTML layout. This section describes general information about creating a backend and the important design details of the three backends that have been implemented so far.

Each backend has its strengths and weaknesses and it is useful to have different options to try if one backend is not producing the desired result.

A 'layoutEngine' backend package only needs to export

one object: a "layoutengine" object that

is created by calling the layoutEngine::makeEngine function.

The makeEngine function has only one required argument,

called layout, which should be a function. That

layout function is called by layoutEngine::flow

to perform the HTML layout.

The layout function is provided with the following

arguments: html, which is the "htmlElement"

object to layout; width and height, which

specify the dimensions of the page for the layout (in inches);

fonts, which names R font families (that will be used

to render the layout); and device, which provides the name

of the device for the layout. The last two arguments are mainly

provided so that they can be used in calls to the helper functions

described below.

How the HTML layout is performed is up to the individual backends, but there are several helper functions provided by the 'layoutEngine' package to help with that task.

The layoutEngine::fontFiles function can be used to

obtain paths to font files based on the fonts argument

that is given to the layout function. This can be useful

to, for example, place copies of the font files in a location that

the backend can access during the HTML layout.

The layoutEngine::copyAssets function can be used to

copy external resources for the HTML layout to a specified directory.

Again, this can be useful for the backend to set up files within the

local file system for the HTML layout.

The layoutEngine::makeLayout function must be used to

generate the final layout result. This takes a number of arguments,

the names of which are available via

names(layoutEngine::layoutFields). The idea is that

each argument contains a different piece of layout information for all

of the nodes in the HTML. All arguments should have the same length,

but many of the arguments can contain NA, and several

should (for example, there are arguments that contain information about

text nodes that should contain NA values for non-text nodes).

This layout result format is the most fragile part of the

'layoutEngine' package and the most likely to experience change.

The makeLayout function provides some level of protection

by making it very likely that any incompatibility between the result

format expected by the

'layoutEngine' package and the layout format generated by a backend

package will result in immediate and spectacular failure.

An optional second argument to the layoutEngine::makeEngine

function, called CSStransforms, allows a backend to

specify a list of functions. If any of these are provided, the

layoutEngine::flow function will call them to transform

specific CSS properties, when generating @font-face rules.

At the time of writing, two transformation functions were looked for:

fontWeight and fontFile. Examples of their

use are described in the sections on individual backends below.

The 'layoutEngineCSSBox' backend is based on the CSSBox Java library (Burget, 2018). The motivation for this backend is that CSSBox was designed for the purpose of generating HTML layout information (rather than for rendering HTML itself). In other words, it is a standalone HTML layout engine.

One advantage that arises from this is in the layout of text within HTML, because CSSBox generates information for every line of text (after layout). This is better than the API provided by most web browsers (see the Section on Defining fonts).

One important detail about this backend is that it generates text layout information at different levels of accuracy based on what sort of device the HTML will be rendered on. For print devices (PDF or PostScript output in R), it will use so-called "fractional metrics" for text layout, but for pixel-based devices (screen or PNG), the text layout information is rounded to whole pixels. This is done so that text positioning looks right on both print and on-screen rendering.

The major downside to CSSBox is that it does not implement as many

CSS properties or support them as well as modern browsers.

For example, CSSBox does not support numeric font-weight

properties and for this reason it defines a

fontWeight function (via the cssTransforms

argument to makeEngine) that converts numeric

font-weight values to "bold" or

"normal".

This backend has no support for modern CSS properties like

shape-outside or CSS Grid Layout and it has no

javascript engine.

The 'layoutEnginePhantomJS' backend is based on the PhantomJS program (Hidayat, 2018), a headless web browser based on the WebKit browser engine (Apple Inc., 2018).

The motivation for this backend is that it is based on a modern web browser engine, so has good support for HTML and CSS features, and a javascript engine, but it does not require a graphical user interface; it can perform HTML layout off-screen.

The major downside to this backend is that development of PhantomJS has recently ceased. Even prior to that, it was always based on a slightly old WebKit engine, so lacked the most up-to-date HTML and CSS features.

The 'layoutEngineDOM' backend is based on the 'DOM' package

(Murrell, 2018b),

which provides communication between R and a web browser

(via web sockets).

A specific web browser can be selected using

options(browser=).

The motivation for this backend is that it provides access to the latest web browsers and thereby the latest HTML and CSS features (and javascript).

The major downside to this backend is that, every time an HTML layout occurs, the HTML is rendered in the web browser that R is communicating with, so a new browser window or tab is created on screen every time (although this can be incredibly useful for debugging).

One important detail about this backend is that (at least some)

web browsers do not support Type 1 fonts (.pfb or

.pfa font files).

This is not unreasonable given that the

W3C Recommendation (Lilley et al., 2018) only mentions

TrueType, OpenType, WOFF (1.0 or 2.0), and SVG Fonts,

but this means that, if we are rendering in R onto a standard

pdf or postscript graphics device,

the Type 1 font files that R will use are not suitable for

the web browser to use.

For this reason, the 'layoutEngineDOM' backend automatically

converts Type 1 fonts to TrueType fonts (using fontforge;

Williams, 2018) and it defines a

fontFile function (via the cssTransforms

argument to makeEngine) that converts the font file

suffixes from .pfb or

.pfa to .ttf.

The 'layoutEngine' package and its three backends provide the ability to render HTML content within R graphics. The examples in the early sections of this document demonstrate that these packages can already perform some useful tasks. However, the packages are all at an early stage of development. They suffer from a number of issues and limitations, which will be discussed in this section.

The packages have been developed and tested on Linux only.

There is no obvious reason why 'layoutEngineCSSBox' should not

also work on Windows, but the other backends rely on

software tools that may not be available on Windows or are at

least cumbersome to install (e.g., fontforge for

'layoutEngineDOM').

The packages have only been designed to work on Cairo-based

R graphics devices, plus pdf and postscript.

Some devices will be extremely difficult to support, at least because of compatibility of fonts. For example, matching or converting X11 fonts for the X11 device to fonts that layout backends can use would be hard.

On the other hand, it should be possible to expand support to more

devices, for example the svg device, which is based on

Cairo graphics (though not explicitly supported by 'layoutEngine' yet).

Support for native Windows and MacOS graphics devices is one of the obstacles to overcome for cross-platform support.

We have already seen that the 'layoutEngine' package only has support

for basic CSS properties at this stage. There is a

very long list

of properties that could be added.

The CSS transform property

is just one example of a property that may take significant

effort to support.

However, the situation is not completely as dire as that long list

of CSS properties would suggest.

This is because the 'layoutEngine' package only needs to provide

explicit support for a subset of CSS properties. Some CSS properties,

like text-align

only affect where

HTML content is rendered and 'layoutEngine' relies on

the backend packages to implement those properties

(and just positions its rendering based on the layout result).

It is only properties such as border-left-style

that affect how the HTML content is rendered that

'layoutEngine' needs to worry about.

That is not to say that the 'layoutEngine' package has a small task to perform. Even apparently straightforward properties like borders have only partial support at present. For example, the following code renders a <div> element with a border that has a different width and colour on top than on the three other sides. The result (at the corners) is not what a web browser produces.

grid.html('<div style="width: 100; height: 50; border-style: solid; border-width: 3; border-color: black; border-top-width: 10; border-top-color: red"/>')

There are also a number of border styles, such as groove,

ridge, inset, and outset

that are not yet supported (they currently get converted to

solid, with a warning).

In HTML layout, the CSS property hyphens can be

used to control hyphenation. By default, the value is

manual, so a line break will only occur

where

there is already an explicit hyphen or where a

special "soft" hyphen (­) has been specified.

However, it is possible to specify the value auto,

in which case (assuming that the web browser has a

hyphenation algorithm/database) the web browser can decide where to

break text all by itself. (Note that the lang

attribute must be set in the <html> element to specify

the language of the document before hyphenation will work.)

This CSS property is not only unsupported at present, but it is not clear how support could be added.

Unfortunately,

CSSBox does not support the hyphens property,

and the technique of wrapping each word in <span>

tags does not help with hyphenation for the other backends.

This means that none of the existing backends can produce layout

information for individual pieces of hyphenated text (and may never

be able to).

The following HTML and CSS code provides a simple demonstration

(the correct behaviour is shown below the incorrect result

from 'layoutEngine').

HTML <- ' <div id="main" style="width: 55px; border-style: solid"> An extremely long English word. </div> ' CSS <- ' div { hyphens: auto; } ' html <- htmlElement(HTML, CSS) grid.html(html)

Many of the values that are returned by HTML layout backends are in "px" units. The 'layoutEngine' package assumes that 1px = 1/96in. This is a simplification of the more subtle CSS definition of "px" units, but should work when the backend is run on a standard computer monitor.

For the layout results from a backend (run on a standard computer

monitor) to render properly on a pixel-based R graphics device, such as the

png device, the resolution of the graphics device should be set

to 96 dpi.

Rendering of HTML content in R is not fast. The potential value of the 'layoutEngine' package is to expand what is possible within R graphics, but it comes at a speed cost.

The rendering performance is doomed to some extent because it is based on a layout engine flowing the HTML content and then R rendering it, which is almost double the normal amount of work. R graphics rendering is also much slower than what would happen in a web browser. There is also the problem that, at least with some backends, individual words of text are rendered in R one at a time.

There should be some places where performance could be improved. For example, the 'layoutEngineDOM' backend converts Type 1 fonts to TrueType fonts every time it performs a layout. Some sort of caching mechanism could reduce the workload there. However, the 'layoutEngine' package is never going to be the fastest way to render HTML content.

The 'layoutEngine' package (together with its backend packages) makes it possible to render HTML content within R graphics. This is useful for producing graphical effects, especially layouts, that are easy or easier to achieve in HTML (even if the HTML code is generated from R) compared to achieving the same result directly in R graphics.

To the author's knowledge, no other package provides this facility for R, though there are many R packages that perform related functions. In particular, R packages that generate HTML output, such as 'xtable' and 'htmltools' (RStudio Inc., 2017), are rich sources of HTML code that the 'layoutEngine' package can then be used to render in R.

There are several R packages that provide an R interface to javascript layout libraries (for arranging HTML content), for example 'RagGrid' (Srikkanth and Praveen, 2018) and 'htmllayout', but these are aimed at producing HTML rendering in a web browser, not in R.

The 'Rcssplot' package (Konopka, 2018) provides CSS styling for R plots, but this is an alternative interface to controlling the appearance of existing R graphics facilities, rather than an interface to new HTML graphics facilities.

Claus Wilke is working on a 'gridtext' package to improve R's text rendering facilities, including support for rich text (simple HTML markup). This overlaps with some of the HTML features that the 'layoutEngine' provides, though with a narrower focus. On the other hand, 'gridtext' requires far less infrastructure and fewer dependencies compared to the 'layoutEngine' package.

The 'layoutEngine' package is far from complete. There are many CSS properties for which support could be added and improved and there are issues such as breaking lines of text and text encodings that require further work (see the Section on Limitations).

There are also many other ways that a backend could be developed for the 'layoutEngine' package. For example, a backend based on Selenium (Project, 2018) (or the 'RSelenium' package; Harrison, 2018) might be a significant improvement on the PhantomJS backend. Another PhantomJS alternative is the SlimerJS headless browser (Jouanneau, 2018). Instead of the 'DOM' backend, something based on 'shiny' (Chang et al., 2017) would almost certainly provide a more stable and mature browser interface (and potentially integration with RStudio; RStudio Team, 2018).

The examples and discussion in this document relate to version 0.1-0 of the 'layoutEngine' package, version 0.1-0 of the 'layoutEngineCSSBox' package, version 0.1-0 of the 'layoutEnginePhantomJS' package, and version 0.1-0 of the 'layoutEngineDOM' package.

The report is also dependent on version 1.0-0 of the 'gyre' font package and version 1.0-0 of the 'courier' font package.

The report is also dependent on the 'cssbox-4.14-mod' branch of a fork of CSSBox, which is required to allow fractional metrics in the HTML layout calculation.

The report is also dependent on

version 0.6-0

of the 'DOM' package. This contains updates for compatibility with

recent versions of the 'httpuv' package (Cheng et al., 2018), a new

head argument for the htmlPage function

(so that we can inject CSS @font-face rules into a page),

and new support for serving files from an assets

directory (so that we can provide external resources such as font files

and image files to a page).

The report is also dependent on

version 0.18 of the 'extrafont' package (which is a fork of Winston Chang's package),

to allow install_font to work with font packages that

contain .pfa files (in addition to the existing support for

.pfb files). This is required for the 'courier' font

package.

This report was generated within a Docker container (see Resources section below).

Murrell, P. (2018). "Rendering HTML Content in R Graphics" Technical Report 2018-13, Department of Statistics, The University of Auckland. [ bib ]

This document

by Paul

Murrell is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.